Luigi Pirandello was born in Caos, near Girgenti, on the island of Sicily, which was to be the inspiration of his writings. “I am a child of Chaos and not only allegorically,” he said in his biographical sketch.. Pirandello’s father, Stefano Ricci-Gramitto, owned a prosperous sulfur mine. His childhood Pirandello spent in modest weath in Girgenti (today called Agrigento) and Palermo, surrounded by nurses and servants, and enjoying the adoration of his mother. From his teens Pirandello showed literary talents, but he first planned to study law. However, his father, intended his son to become a businessman.

Italian author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934 for his “bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage.” Pirandello’s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and c. 40 plays, some of which are written in Sicilian dialect. Typical for Pirandello is to show how art or illusion mixes with reality and how people see things in very different way – words are unrealiable and reality is at the same time true and false. Pirandello’s tragic farces are often seen as forerunners for theatre of the absurd. A man will die, a writer, the instrument of creation: but what he has created will never die! And to be able to to live for ever you don’t need to have extraordinary gifts or be able to do miracles. Who was Sancho Panza? Who was Prospero? But they will live for ever because – living seeds – they had the luck to find a fruitful soil, an imagination which knew how to grow them and feed them, so that they will live for ever.” (from Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1921).

Luigi Pirandello was born in Caos, near Girgenti, on the island of Sicily, which was to be the inspiration of his writings. “I am a child of Chaos and not only allegorically,” he said in his biographical sketch. Pirandello’s father, Stefano Ricci-Gramitto, owned a prosperous sulfur mine. His childhood Pirandello spent in modest weath in Girgenti (today called Agrigento) and Palermo, surrounded by nurses and servants, and enjoying the adoration of his mother. From his teens Pirandello showed literary talents, but he first planned to study law. However, his father, intended his son to become a businessman.

In 1887 Pirandello entered the University of Rome, from where he was expelled for offending a Latin professor, and then transferred to the University of Bonn, Germany, receiving his doctoral degree in Roman philology in 1891. Pirandello’s dissertation, written in Germany, dealt with the dialect of his native region.

After having a liaison with his cousin Linuccia, which his father did not approve, Pirandello started his career as a writer. “Blessed is he who can stop halfway and before old age comes on can marry illusion and preserve it lovingly,” Pirandello wrote in 1887 in a letter of his future plans. In Rome, where he had settled with a montly allowance from his father, Pirandello translated Goethe’s Roman Elegies, wrote ELEGIE RENANE (1895), and published two collections of poetry, and a collection of short stories, AMORI SENZ’AMORE (1894). In 1898 he became a professor of Italian literature at a teacher’s college for women, and worked there for 24 years. L’ESCLUSA (1901) was Pirandello’s first full-length novel. In the ironical story the protagonist suspects that his wife is unfaithful and takes her back after the adultery has actually occurred.

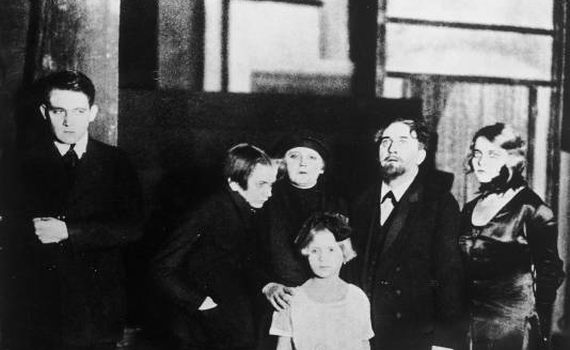

Pirandello had married in 1894 Antonietta Portulano, a fellow Sicilian and the daughter of his father’s business associate. She suffered mental breakdown in 1904. When her condition steadily worsened – she became insane with a jealous paranoia – the illness deeply influenced Pirandello’s writing. During World War I, both of Pirandello’s sons were captured as prisoners of war.

After his wife’s illness got worse, Pirandello was forced to place her in 1919 in a mental institution. When the collapse of the sulfur mines destroyed the family business, Pirandello had to turn his writing into a financially profitable activity.

In 1904 Pirandello gained his first literary success with the novel IL FU MATTIA PASCAL. Its antihero, Mattia Pascal, is mistakenly declared dead. Offered an opportunity to start life over again, he escapes from his family. In Montecarlo Mattia wins a fortune, but his newly found freedom turns sour and he must return to his hometown, to his past he had hoped to leave behind.

“I can’t really say that I’m myself,” he thinks. “I don’t know who I am. . . . I am the late Mattia Pascal.” In the following decades the questions “who am I?” and “what is real?” became central in Pirandello’s fiction.

UNO, NESSUNO E CENTOMILA (1925-26, One, None, and Hundred-Thousand), a story about husband’s descend into madness, owed more to Freud than Gogol. His despair starts when his wife comments a slight defect on his nose – it tilts to the right.

Pirandello started to write plays as early as in the 1880s, but he first considered the stage insensitive medium compared to the novel. After 1915, Pirandello concentrated on the theater and wrote until 1921 sixteen dramas.

LA RAGIONE DEGLI ALTRI (1915) was Pirandello’s first three-act play. It did not gain much understanding, but through the performances of the actor Angelo Musco (1892-1937) his work started to attract attention.

His ideal female lead Pirandello found in Marta Abba, for whom he wrote several plays, among them DIANA E LA TUDA (1926, Diana and Tuda), L’AMICA DELLE MOGLI (1927, The Wives’s Friend), and COME TU MI VUOI (1930, As You Desire Me). Pirandello also engaged her for his own company, the Teatro d’Arte di Roma, and formed a relationship with her, documented in Pirandello’s Love Letters to Martha Abba (1994).

COSI È (SE VI PARE) (Right You Are – If You Think You Are), published in 1918, marked Pirandello’s interest in the examination of the relativity of truth. The story was about a woman whose identity remains hidden and who could be one of the two very different people.

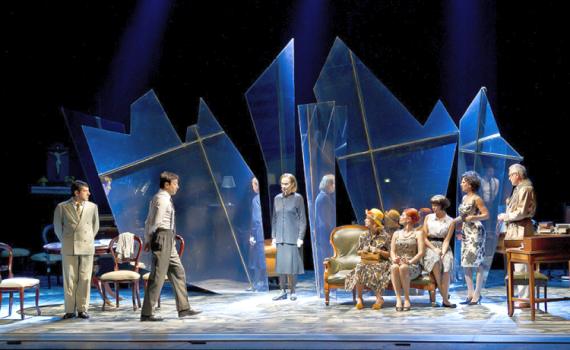

SEI PERSONAGGI IN CERCA D’AUTORE (1921, Six Chracters in Search of An Author) asked the question, can fictional characters be more authentic than real persons, and what is the relationship between imaginary characters and the writer, who has created them. Six Characters in Search of an Author consists of roles-within-roles. In rehearsal preparations of a theatrical company are interrupted by the Father and his family who explain that they are characters from an unfinished dramatic works. They want to interpret again crucial moments of their lives, claiming that they are “truer” than the “real” characters.

“How can we understand each other if the words I use have the sense and the value I expect them to have, but whoever is listening to me inevitably thinks that those same words have a different sense and value, because of the private world he has inside himself too. We think we understand each other: but we never do,” says the Father.

He tells that he has helped his wife to start a new life with her lover and the three illegitimate children born to them.

The Wife claims that he forced her into the arms of another man.

The Stepdaughter accuses the Father for her shame – they met before in Mme Pace’s infamous house, and he did not recognize her. She was forced to turn to prostitution to support the family.

The Son refuses to acknowledge his family and runs into the garden. He shots himself and the actors argue about whether the boy is dead or not. The Father insists that the events are real.

The Producer says: “Make-believe?! Reality?! Oh, go to hell the lot of you! Lights! Lights! Lights!” and The Stepdaughter escapes into the audience laughing maniacally.

Six Chracters in Search of An Author created a scandal when it was first performed in Rome, but it was hailed as a masterpiece in Paris, innovatively produced by Georges Pitoëff. G.B. Shaw praised it as the most original play ever.

ENRICO IV (1922, Henry IV, known in the United States as The Living Mask), premiered in Milan, received much better reception. The play told about a man who has fallen from his horse during a masquerade and starts to believe he is the German emperor Henry IV. To accommodate his illness his wealthy sister has placed him in a medieval castle surrounded by actors dressed as eleventh-century courtiers. The nameless hero regains his sanity after twelve years, but decides to pretend he is mad.

With the trilogy Six Characters in Search of An Author, in which the characters of the title are called into existence by a writer, CIASCUNO A SUO MODO (1924) and QUESTA SERA SI RECITA A SOGGETTO (1930), Pirandello revolutionized the modern theatrical techniques.

A second trilogy, LA NUOVA COLONIA (1928), LAZZARRO (1929), and I GIGANTI DELLA MONTAGNA (1934, The Mountain Giants) moved from the limits of truth-telling to the reality outside of art. The Mountain Giants was left unfinished. It portrayed a magician, who lives in an abandoned villa. A theatrical company decides to perform at a celebration given by the ‘Giants of the Mountain‘. The barbaric audience tears two of the actors to pieces and kills one of the directors of the company.

Pirandello once said: “I hate symbolic art in which the presentation loses all spontaneous movement in order to become a machine, an allegory – a vain and misconceived effort because the very fact of giving an allegorical sense to a presentation clearly shows that we have to do with a fable which by itself has no truth either fantastic or direct; it was made for the demonstration of some moral truth.” (from Playwrights on Playwriting, ed. by Toby Cole, 1961).

Pirandello’s central themes, the problem of identity, the ambiguity of truth and reality, has been compared to explorations of Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, but he also anticipated Beckett and Ionesco. One of the earliest formulations of his relativist position Pirandello presented in the essay ‘Art and Consciousness Today‘ (1893), in which he argued that the old norms have crumbled and the idea of relativity deprives “almost altogether of the faculty for judgment.” A central concepts in his work is “naked mask“, referring our social roles and on the stage the dialectic relationship between the actor and the character portrayed. In Six Characters the father points out, that a fictional figure has a permanence that comes from an unchanging text, but a real-life person may well be “a nobody“. Pirandello did not only restrict his ideas to theatre acting, but noted in his novel SI GIRA (1915), that the film actor “feels as if in exile – exiled not only from the stage, but also from himself.“

In 1923 Pirandello requested membership in the Fascist party and obtained Mussolini’s support in founding the National Art Theatre of Rome (Teatro d’Arte di Roma). However, the company was closed in 1928 on grounds of financial problems.

In 1934 Pirandello’s libretto for Gian Francesco Malipiero’s opera The Fable of the Changeling was criticized by the Fascist authorities. Pirandello had first seen in Mussolini a man committed to the facts rather than theory, but later he described Mussolini as “as top hat, and empty top hat that by itself cannot stand upright“. Remaining critical towards the regime, he did not support the Ethiopian invasion by Italy. Pirandello died in Rome on December 10, 1936.

Pirandello’s influence can be seen on such European and American writers as Jean Anouilh, Jean-Paul Sartre, Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, Jean Genet, Eugene O’Neill, and Edward Albee. In Latin America, Jorge Luis Borges’s questioning of the nature of identity have much in common with Pirandellian themes. Several of Pirandello’s works have been adapted into screen, including As You Desire Me (1932), starring Greta Garbo, L’homme de nulle part (1937), based on the novel The Late Mathias Pascal and directed by and Pierre Chenal. Kaos, directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani (1984), was based on the author’s four Sicilian stories.

For further reading: Characters and Authors in Luigi Pirandello by Ann Caesar (1998); Luigi Pirandello, 1867-1936, His Plays in Sicilian by Joseph F. Privitera (1998); Luigi Pirandello: The Theatre of Paradox, ed. by Julie Dashwood (1997); Ars dramatica: Studi sulla poetica di Luigi Pirandello by Rena A. Lamparska (1997); Understanding Luigi Pirandello by Fiora A. Bassanese, James N. Hardin (1997); Pirandello & Film by Nina Davinci Nichols, et al (1995); A Companion to Pirandello Studies, ed. by John Louis Digaetani (June 1991); Moments of Selfhood by James V. Biundo (1990); Luigi Pirandello by S. Bassnett-McGuire (1983); Luigi Pirandello: an Approach to his Theatre by O. Ragusa (11000); Dreams of Passion: The Theater of Luigi Pirandello by R, Oliver (1979); Introduzione alla critica pirandelliana by A. Illano (1976); Pirandello: a Biography by G. Giudice (1975); Pirandello fascista by G.F. Vené (1971); Luigi Pirandello by G. Giudice (1963); L’ arte di Luigi Pirandello by F. Puglisi (1958); Playwrights on Playwrighting, ed. by Toby Cole (1961); Luigi Pirandello by L. Ferrante (1958); Luigi Pirandello by L. Baccalo (1949); L’ Uomo segreto by F.V. Nardelli (1944); L’opera di Luigi Pirandello by M. Lo Vecchio Musti (1939) – Suomeksi Pirandellolta on käännetty useita näytelmiä ja esseekokoelma Uusi teatteri ja vanha teatteri (1934).

Pirandello’s Biography (in Italian)

Se vuoi contribuire, invia il tuo materiale, specificando se e come vuoi essere citato a

collabora@pirandelloweb.com