A comedy in the making in three acts.

Six Characters in Search of an Author created Luigi Pirandello’s international reputation in the 1920s and is still the play by which he is most widely identified. With originality that was startling to his contemporaries, Pirandello introduced a striking and compelling dramatic situation that initially baffled but eventually dazzled audiences and critics alike.

Introduction, Analysis, Summary

Pirandello’s preface

Characters, Act I

Act II

Act III

In Italiano – Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore

En Español – Seis personajes en busca de autor

Introduction – Short summary – Characters analysis – Plot Summary

Themes and style – Critical overwiev – Criticism

Introduction

Six Characters in Search of an Author created Luigi Pirandello’s international reputation in the 1920s and is still the play by which he is most widely identified. With originality that was startling to his contemporaries, Pirandello introduced a striking and compelling dramatic situation that initially baffled but eventually dazzled audiences and critics alike. In what begins as a realistic play he introduces six figures who make the extraordinary claim that they are the incomplete but independent products of an artist’s imagination – “characters” the artist abandoned when he couldn’t complete their story. These “characters” have arrived on the stage to find an author themselves, someone who will give them the fullness of literary life that their original author has denied them. Furthermore, these “characters” claim that they are more “real” than the actors who eventually want to portray them. This concept was so startling it helped to incite a riot in the audience when the original production of the play was staged in Rome on May 10, 1921. Later that year, however, audiences and critics had assimilated the extraordinary idea and were enchanted by a remounted production in Milan. The play would then see successful productions in London and New York in February and October of 1922, in Paris in 1923, and in Berlin and Vienna in 1924. Pirandello’s own theatre company, founded in 1925, then performed the play in Italian throughout the major cities of Europe and North and South America. As a result of this assault on the theatre world, Pirandello became one of the most respected and influential dramatists in the world by the end of the 1920s, and today Six Characters in Search of an Author is considered one of the most influential plays in the history of world literature.

No sex, no death, but there’s plenty of passion in this play about identity and relative truths. Pirandello wrote Right you are (If you think so) in 1917, before his more famous Six Characters in search of an author (1921). In Right you are, seven characters–he liked to deploy more than the customary two or three on stage at a time–seven respectable, middle-class types in a comfortable, bourgeois parlor argue over their perceptions of a mysterious woman seen at the window of a nearby building. That’s all that happens. Yet the play offered a blueprint to many works thereafter, including the brilliant Japanese film, Rashomon.

The performance, a rare treat for New York audiences, never felt dated. Rather, Pirandello is not performed often enough, although every critic of note acknowledges that his plays revolutionized theater. Argument, or debate, is of course the oldest form of drama. What made Right you are timely was its intellectual “conceit,” or central idea, that all is relative; individual perceptions can never reach unanimity.

G.B. Shaw in England and Luigi Pirandello in Italy perfected the strategy of dramatizing ideas that were floating free in the intellectual climate: in this they were more than standard bearers of modernism and modernity. Absolutes at the core of science and philosophy had been crumbling well before Right you are. By the turn of the century, subjectivity had replaced objectivity as the stance from which to see and evaluate the world and human behavior as well.

Einstein, after seeing a performance of Six Characters in search of an author, greeted Pirandello backstage saying, “We are soul-mates.” The anecdote may be apocryphal, but the point about relativity remains an apt comment on the theme in Six Characters and Right you are as well. It was one of Pirandello’s favorite subjects.

New York, December 5, 2003

Short summary

A group of actors are preparing to rehearse for a Pirandello play. While starting the rehearsal, they are interrupted by the arrival of six characters. The leader of the characters, the father, informs the manager that they are looking for an author. He explains that the author who created them did not finish their story, and that they therefore are unrealized characters who have not been fully brought to life. The manager tries to throw them out of the theater, but becomes more intrigued when they start to describe their story. The father is an intellectual who married a peasant woman (the mother). Things went well until she fell in love with his male secretary. Having become bored with her over the years, the father encouraged her to leave with his secretary.

She departs from him, leaving behind the eldest son who becomes bitter for having been abandoned. The mother starts a new family with the other man and has three children. The father starts to miss her, and actively seeks out the other children in order to watch them grow up. The step-daughter recalls that he used to wait for her after school in order to give her presents. The other man eventually moves away from the city with the family and the father loses track of them. After the other man dies, the mother and her children return to the city. She gets a job in Madame Pace’s dress shop, unaware that Madame Pace is more interested in using her daughter as a prostitute.

One day the father arrives and Madame Pace sets him up with the daughter. He starts to seduce her but they are interrupted when the mother sees him and screams out. Embarrassed, he allows the step-daughter and the entire family to move in with him, causing his son to resent them for intruding in his life. The manager agrees to become the author for them and has them start to play the scene where the father is in the dress shop meeting the step-daughter for the first time. He soon stops the plot and has his actors attempt to mimic it, but both the father and the step-daughter protest that it is terrible and not at all realistic. He finally stops the actors and allows the father and step-daughter to finish the scene. The manager changes the setting for the second scene and forces the characters to perform it in the garden of the father’s house. The mother approaches the son and tries to talk to him, but he refuses and leaves her. Entering the garden, he sees the youngest daughter drowned in the fountain and rushes over to pull her out. In the process, he spots the step-son with a revolver. The young boy shoots himself, causing the mother to scream out for him while running over to him. The manager, watching this entire scene, is unable to tell if it is still acting or if it is reality. Fed up with the whole thing, he calls for the end of the rehearsal.

Characters analysis

Amalia

See The Mother

The Director

See The Producer

The Father

The Father is the leading spokesperson for the six “characters.” He is the biological father of the 22 year-old son he had with the Mother, and he is the stepfather of the three children the Mother had during her relationship with the Father’s secretary. In his “Preface” to Six Characters in Search of an Author, Pirandello describes the Father as “a man of about fifty, in black coat, light trousers, his eyebrows drawn into a painful frown, and in his eyes an expression mortified yet obstinate.” The Father is mortified by his stepdaughter’s charge that he has felt incestuous feelings for her since she was a child, stalking her when she was a schoolgirl, and attempting to buy her in Madame Pace’s brothel. The Father insists that his concern for his family has always been genuine and that he was surprised to discover his stepdaughter at Madame Pace’s establishment. The Father is determined to have their story told. According to Pirandello, the Father and Stepdaughter are the “most eager to live,” the “most fully conscious of being characters,” and the “most intensely alive” as the two of them “naturally come forward and direct and drag along the almost dead weight of the others.”

The Little Boy

The Little Boy is 14 years old and the eldest son of the Mother from her relationship with the Father’s secretary. The Little Boy is dressed in mourning black, like his mother and two sisters, in memory of the death of his natural father. He is timid, frightened, and despondent because in his short stay in the Father’s house following the incident in Madame Pace’s brothel he was intimidated by the Father’s natural son. His elder sister, the Stepdaughter, also disdains the Little Boy because of his action at the end of their story. The Little Boy does not speak because he is a relatively undeveloped character from the author’s mind, and in the “Preface” Pirandello lumps the Little Boy with his younger sister as “no more than onlookers taking part by their presence merely.” At the end of the story, the Little Boy will shoot himself with a revolver when he sees his little sister drowned in the fountain behind his stepfather’s house.

The Little Girl<

About four years old, the youngest daughter of the Mother from her relationship with the Father’s secretary, the Little Girl is dressed in white, with a black sash around her waist. For the same reason as with her brother, the Little Girl does not speak, and she will drown at the end of the story presented by the “characters.”

The Mother

The wife of the Father and the mother of all four children (the eldest son by the Father and the other three by the lover who has just died). She is dressed in black with a widow’s crepe veil, under which is a waxlike face and sad eyes that she generally keeps downcast. Her main goal is to reconcile with her 22-year-old “legitimate” son, to convince him that she did not leave him of her own volition. The Mother is deeply ashamed of the Father’s experience with her eldest daughter in Madame Pace’s brothel. According to Pirandello in the “Preface,” the Mother, “entirely passive,” stands out from all the others because “she is not aware of being a character. . . not even for a single moment, detached from her ‘part.’” She “lives in a stream of feeling that never ceases, so that she cannot become conscious of her own life, that is to say, of her being a character.”

Other Actors, Actresses, and Company Members

The other members of the Producer’s company are proud of their craft and initially contemptuous of the six “characters” but then become quite intrigued by their story and are anxious to portray it.

Madame Pace

The owner of the dress shop that doubles as a brothel, Madame Pace is old and fat and is dressed garishly and ludicrously in silk, wearing an outlandish wig and too much makeup. She speaks with a thick Spanish accent and is mysteriously summoned by the Father when she appears to be missing from the brothel scene between the Father and Stepdaughter. She is, essentially, the “seventh” of the “characters.” In the “Preface” Pirandello points out that as a creation of the moment Madame Pace is an example of Pirandello’s “imagination in the act of creating.”

The Producer

The Producer (or Director or Stage Manager, depending on the text and translation that is used) is the main voice for the theatrical company that is attempting an afternoon rehearsal for their current production when the six “characters” enter and request their own play to be done instead. The Producer initially attempts to dismiss these “people” as lunatics, intent on getting his own work done. Gradually, however, he becomes intrigued by the content of their story and comes to accept their “reality” without further questioning because he sees in their story the potential for a commercial success. An efficient and even violently gruff man, the Producer is also patient, flexible, and courageous, willing to go forward without a great deal of conventional understanding of where things are taking him. He is, however, comically inflexible in that he insists on modifying what the “characters” give him to fit the stage conventions to which he is accustomed.

Rosetta

See The Little Girl

The Son

The only biological child of both the Mother and Father, this tall 22-year-old man was separated from his mother at the age of two and was raised and educated in the country. When he finally returned to his father, the Son was distant and is now contemptuous of his father and hostile toward his adopted family. Pirandello describes him as one “who stood apart from the others, seemingly locked within himself, as though holding the rest in utter scorn.”

The Stage Manager

See The Producer.

The Stepdaughter

he Stepdaughter is 18 years old and the eldest child from the Mother’s relationship with the Father’s secretary. After her natural father died, the Stepdaughter was forced into Madame Pace’s brothel in order to help the family survive, and it was at the brothel that she encountered her stepfather. Pirandello describes her as “pert” and “bold” and as one who “moved about in a constant flutter of disdainful biting merriment at the expense of the older man (the Father).” Desiring vengeance on the Father, the Stepdaughter is elegant, vibrant, beautiful, but also angry. She, too, is dressed in mourning black for her natural father, but shortly after she is introduced to the Producer and his company, she dances and sings a lively and suggestive song. The Stepdaughter dislikes the 22-year-old son because of his condescending attitude toward her and her “illegitimate” siblings, and she is also contemptuous of her 14 year-old brother because he permitted the Little Girl to drown and then “stupidly” shot himself. She is, however, tender toward her four-year-old sister. The Stepdaughter and the Father are the author’s two most developed characters and thus dominate the play.

Plot Summary

Act I

When Six Characters in Search of an Author begins, the stage is being prepared for the daytime rehearsal of a play and several actors and actresses are milling about as the Producer enters and gets the rehearsal started. Suddenly the guard at the stage door enters and informs the Producer that six people have entered the theatre asking to see the person in charge. These six “characters” are a Father, a Mother, a 22-year-old Son, a Stepdaughter, an adolescent Boy, and young female Child. These “characters” claim that they are the incomplete creations of an author who couldn’t finish the work for which they were conceived. They have come looking for someone who will take up their story and embody it in some way, helping them to complete their sense of themselves. The Producer and his fellow company members are initially incredulous, convinced that these “people” have escaped from a mental institution. But the Father, speaking for the other characters, argues that they are just as “real” as the people getting ready to rehearse their play. Fictional characters, he maintains, are more “alive” because they cannot die as long as the works they live in are experienced by others. The Father explains that he and the other “characters” want to achieve their full life by completing the story that now only exists in fragments in the author’s brain. The Stepdaughter and Father begin to tell their “story.” The Father was married to the Mother but left her many years ago when she became attracted to a young assistant or secretary in his employ. Though the Father was angered by his wife’s feelings and sent his young assistant away, he grew impatient with his wife’s melancholy and sent their son away, to be raised and educated in the country. He eventually turned his wife out and she sought her lover, bearing three more children by him before the man died two months before the play begins. These three children and the son from her marriage with the Father stand before the Producer and his theatrical troupe.

The Father’s version of these events is variously contested both by the Mother and the Stepdaughter. The Father claims that he turned his wife out because of his concern for her and his natural son and that later he was genuinely concerned for his wife’s new family. However, the Mother claims the Father forced her into the arms of the assistant because he was simply bored with her, and the Stepdaughter claims that the father stalked her sexually as she was growing up. They all agree that eventually the Father lost track of his stepchildren because the wife’s lover took different jobs and moved repeatedly.

When the lover died, the family fell into extreme financial need and the father happened upon his Stepdaughter in Madame Pace’s brothel where the Stepdaughter was attempting to raise money to support the family.

Both the Father and Stepdaughter are anxious to play the scene in the brothel because both think the portrayal will demonstrate their version of that meeting. The daughter asserts that the father knew who she was and desired her incestuously while the father claims he did not know her and immediately refused the sexual union when he recognized her – even before the Mother discovered them in the room. After the incident, the Father took his wife and stepchildren home, where his natural son resented their implicit demands on his father. The Producer and actors become intrigued by this story and are anxious to play it, putting aside their original skepticism about whether or not these “people” are “real.” The Producer requests the “characters” to come to his office to work out a scenario.

Act II

The Producer’s plan is for the “characters” to act out their story, starting with the scene in Madame Pace’s brothel, while the prompter takes down their dialogue in shorthand for the actors of the company to study and imitate. The “characters” suggest that they can act out the story more authentically, but the Producer insists on artistic autonomy and overrules their objections. It is soon discovered that Madame Pace is not available for the scene, but the Father entices her into being by recreating the hat rack in her brothel and she appears – much to the consternation of the acting company, who immediately consider it some kind of trick. When they begin the scene in the brothel, the Producer is initially dissatisfied with Madame Pace’s performance and the Mother disrupts the scene with her consternation over what’s being acted out, but finally the Producer is pleased with what he sees and asks the actors to take over for the Father and Stepdaughter. However, the Stepdaughter cannot help but laugh when she sees how the actors represent their scene in such a different manner from the way she sees it herself. But when the Father and Stepdaughter resume the acting themselves, the Producer censors the scene by not permitting the Stepdaughter to use a line about disrobing. He explains that such suggestiveness would create a riot in the audience. The Stepdaughter accuses the Producer of collaborating with the Father to present the scene in a way that flatters him and misrepresents the truth of what the Father had done. The Stepdaughter asserts that to present the drama accurately the suffering Mother must be excused. But as the Mother is explaining her torment, the final confrontation of the scene is actually played out, with the Mother entering the brothel to discover the Stepdaughter in the Father’s arms. The Producer is pleased with the dramatic moment and declares that this will be the perfect time for the curtain to fall. A member of the stage crew, hearing this comment, mistakes it for an order and actually drops the curtain.

Act III

When the curtain rises again, the scene to be acted out is in the Father’s house after the discovery at the brothel. The Producer is impatient with the suggestions given him by the “characters” about how to play the scene while the “characters” don’t like references to stage “illusion,” believing as they do that their lives are real. The Father points out to the Producer that the confidence the Producer has about the reality of his own personal identity is an illusion as well, that the key elements of his personality and identity change constantly while those of the “characters” stay constant. The Producer decides that regardless of what the “characters” want to propose, the next action will be played with everyone in the garden. After considerable squabbling between the “characters” as to how the scene should be portrayed and after the revelation that the Little Boy has a revolver in his pocket, the Son reluctantly begins telling the story of what he saw when he rushed out of his room and went out to the garden. Behind the tree he saw the Little Boy “standing there with a mad look in his eyes… looking into the fountain at his little sister, floating there, drowned.” Suddenly, a shot rings out on stage and the Mother runs over toward the Boy and several actors join her, discover the Boy’s body, and carry him off. It appears to some actors that this “character” is actually dead, but other actors cry that it’s only make-believe. The exasperated Producer exclaims that he has lost an entire day of rehearsal and the play ends with a tableaux of the “characters,” first in shadow with the Little Girl and Little Boy missing, and then in a trio of Father, Mother, and Son with the Stepdaughter laughing maniacally and exiting the theatre.

Media Adaptations

-

Six Characters in Search of an Author was presented in a full-length film version in 1992 by BBC Scotland, starring John Hurt as the Father, Brian Cox as the Producer, Tara Fitzgerald as the Stepdaughter, and Susan Fleetwood as the Mother. Adapted by Michael Hastings and produced by Simon Curtis, the film was directed by Bill Bryden. In 1996, the 110 minute film was released on videocassette with a teacher’s guide.

-

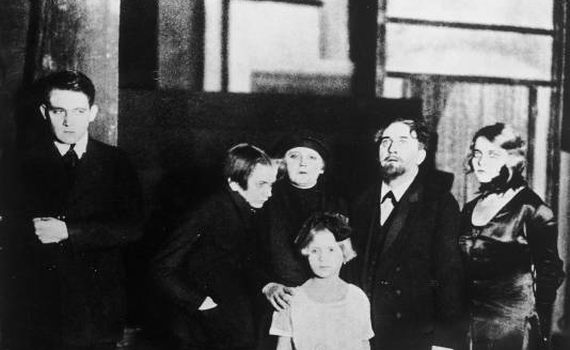

In 1987, sections of Six Characters in Search of an Author were represented in an episode on Pirandello for the BBC Channel 4 South Bank Show series called The Modern World: Ten Great Writers. This documentary recreated a day in the life of Pirandello’s acting troupe as they brought Six Characters in Search of an Author to London in 1925. The show was written and adapted by Nigel Wattis and Gillian Greenwood and produced and directed by Nigel Wattis. Hosted by series editor Melvyn Bragg, the episode featured Jim Norton as Pirandello, Douglas Hodge as the Producer, Reginald Stewart as the Father, Sylvestra LeTouzel as the Stepdaughter, and Patricia Thorns as the Mother.

-

A 59-minute videocassette version of Six Characters in Search of an Author was presented in 1978 as part of an educational television series called Drama: Play, Performance, Perception, hosted by Jose Ferrer. A co-production of Miami-Dade Community College, the BBC, and the British Open University, the episode was directed by John Selwyn Gilbert and included actors Charles Gray, Nigel Stock, and Mary Wimbush. The film was also distributed in 1978 by Insight Media and Films Inc. with actor Ossie Davis as guest commentator and additional direction by Andrew Martin. This version was re-released in 1992 as a 60 minute videocassette.

-

A 48-minute audiovisual cassette version of the play was presented by the British Broadcasting Corporation in cooperation with the British Open University in 1976.

-

A 58-minute VHS videocassette version of the play was produced in 1976 by Films for the Humanities (Princeton, New Jersey) in their History of Drama series as an example of Theatre of the Absurd. It was produced by Harold Mantell, directed by Ken Frankel, translated by David Calicchio, and narrated by Joseph Heller, with music by William Penn. The actors included Nikki Flacks, Ben Kapen, Gwendolyn Brown, Dimo Comdos, Bob Picardo, and Kathy Manning. In the same year this version was also released on two reels of 16 mm film with accompanying textbook, teacher’s guides, and two film-strips. The film was re-released in 1982 in Beta and VHS, in 1988 in VHS, and in 1988 in a 52-minute version.

-

A commentary on the play by Alfred Brooks called “Pirandello’s Illusion Game” was released on audiocassette in 1971 from the Center for Cassette Studies.

-

A 38-minute commentary on the play on audiocassette by Paul D’Andrea was released in 1971 by Everett and Edwards out of Deland, Florida, in the Modern Drama Cassette Curriculum series. Another commentary by Robert James Nelson was released in 1973 as part of their World Literature Cassette Curriculum series.

-

A production of Six Characters in Search of an Author appeared on BBC television on April 20, 1954 in a translation by Frederick May.

Themes and style

Themes

Reality and Illusion

In the stage directions at the beginning of Act I of Six Characters in Search of an Author, Pirandello directs that as the audience enters the theatre the curtain should be up and the stage bare and in darkness, as it would be in the middle of the day, “so that from the beginning the audience will have the feeling of being present, not at a performance of a properly rehearsed play, but at a performance of a play that happens spontaneously.”

The set, then, is designed to blur the distinction between stage illusion and real life, making the play seem more realistic, but Pirandello has no intention of writing a realistic play. In fact, he ultimately wants to call attention as much as possible to the arbitrariness of this theatrical illusion and to challenge the audience’s comfortable faith in their ability to discern reality both in and outside the theatre. Pirandello is concerned from the outset with the relationship between what people take for reality and what turns out to be illusion.

The audience has entered the theatre prepared to see an illusion of real life and to “willingly suspend their disbelief” in order to enjoy and profit from the fiction. In this way, human beings have long accustomed themselves to the illusion of reality on a stage, but in becoming so accustomed they have taken stage illusion for granted and in life they often take illusion for reality without realizing it.

Furthermore, in life, as on stage, the arbitrariness of what is taken for reality is so pervasive as to bring into question one’s very ability to distinguish at all between what is real and what is not. When the action of the play officially begins, the audience knows they are watching actors pretending to be actors pretending to be characters in a rehearsal, but nothing can prepare an audience for the suspension of disbelief they are asked to make when the six “characters” arrive and claim that they are “real.” The audience “knows” these are simply more actors, but the claim these “characters” make is so strange as to be compelling. Even before there are words on a page (not to mention rehearsals, actors, or a performance) these “characters” claim to have sprung to life merely because their author was thinking about them; they claim to have wrested themselves from his control and are seeking out these thespians to find a fuller expression of who they are. These claims understandably strain the credulity of the Producer and the members of his company, who perhaps speak for the audience when they say, “is this some kind of joke?” and “it’s no use, I don’t understand any more.”

The “characters” insist to the end that they are “real” even though the audience “knows” they are actors, and this conflict between what is known and what is passed off as real is intensified by the actors’ responses to crucial moments in the play.

In Act I, for example, the Stepdaughter is summarizing the “story” of these “characters” when the Mother faints with shame and the actors exclaim, “is it real? Has she really fainted?” It is a question the audience would like to dismiss easily – “knowing” that everyone on stage is an actor – but this question is raised again even more dramatically at the end of the play when a real-sounding shot is fired and the Mother runs in the direction of her child with a genuine cry of terror. The actors crowd around “in general confusion,” and the Producer moves to the middle of the group, asking the question that the audience, in spite of its certainty, is tempted to ask, “is he really wounded? Really wounded?” An actress says, “he’s dead! The poor boy! He’s dead! What a terrible thing!” and an actor responds, “What do you mean, dead! It’s all make-believe. It’s a sham! He’s not dead. Don’t you believe it!” A chorus of actor voices expresses the duality that Pirandello refuses to resolve: “Make-believe? It’s real! Real! He’s dead!” says one, and “No, he isn’t. He’s pretending! It’s all make-believe” says another. The Father, of course, assures everyone that “it’s reality!” and the Producer expresses a simple refusal to decide: “Make believe?! Reality?! Oh, go to hell the lot of you! Lights! Lights! Lights!”

Permanence and the Concept of Self

Pirandello was convinced that in real life much is taken for real which should not be. He had only to think of his insane wife’s decades of groundless accusations to realize that what the mind takes to be true is often outrageously false. But if illusions are repeated often enough, believed long enough, and enough people take them to be real, illusions develop a compelling reality in the culture at large. Such, for example, is the commonly held belief in the permanence of a personal identity. Most people believe that they exist as a relatively stable personality, that they are basically the same people throughout their lives. But Pirandello and the Father directly challenge this belief when the Father asks the Producer in Act III “do you really know who you are?” The Producer blubbers, “what? Who I am? I am me!” But the Father undermines this self-assurance by pointing out that on any particular day the Producer does not see himself in the same way he saw himself at another time in the past. All people can remember ideas that they don’t have any more, illusions they once fervently believed in, or simply things that look different now from the way they once appeared to be. The Father leads the Producer to admit that “all these realities of today are going to seem tomorrow as if they had been an illusion,” that “perhaps you ought to distrust your own sense of reality.” Trapped by these observations, the Producer cries, “but everybody knows that (his reality) can change, don’t they? It’s always changing! Just like everybody else’s!” This question of a permanent personal identity is crucial to the Father because the Stepdaughter is trying to characterize him as a lecherous and even incestuous man. The Father knows that “we all, you see, think of ourselves as one single person: but it’s not true: each of us is several different people, and all these people live inside us. With one person we seem like this and with another we seem very different. But we always have the illusion of being the same person for everybody and of always being the same person in everything we do. But it’s not true! It’s not true!” The psychological and physiological needs that led the Father to the brothel were a part of him he does not value; but other people, like his stepdaughter and former wife, choose to define him by this weak moment. “We realise then, (he says) that every part of us was not involved in what we’d been doing and that it would be a dreadful injustice of other people to judge us only by this one action as we dangle there, hanging in chains, fixed for all eternity, as if the whole of one’s personality were summed up in that single, interrupted action.” The Father regrets the incident at Madame Pace’s brothel but asserts that a human being cannot be defined as a consistent personal identity. The reality is that a human being (from the real world at least) changes so drastically from day to day that he cannot be said to be the same person at any time in his life. A human being is perhaps different hour by hour and may end up being 100,000 essentially different people before his life has ended.

Style

The Play Within the Play

The most obvious device that Pirandello uses to convey his themes is to portray the action as a play within a play. The initial play within a play is relatively easy for the audience to handle – Pirandello’s own Rules of the Game is being performed in rehearsal by a troupe of actors. Then the “characters” enter and they seem to embody a completely different play within the play. Furthermore, they insist on acting out the story that have brought to the rehearsal, which is done twice, once by themselves and again by the actors. And once the audience has more or less assimilated all of this, a seventh character, Madame Pace, is created on the spot, as if out of thin air. The effect is similar to that presented with nesting boxes, one inside another and another inside that until the audience gets so far away from their easy faith in their ability to distinguish between reality and illusion that they might throw up their hands like the Producer and simply say, “Make believe?! Reality?! Oh, go to hell the lot of you! Lights! Lights! Lights!” Throughout the production of Six Characters in Search of an Author the audience in fact experiences the difficulty of distinguishing between reality and illusion that constitutes Pirandello’s main theme. And the Producer’s company of actors in many ways speaks for the audience throughout – from the initial, derisive incredulity at the entrance of the “characters” to the ambivalent response at the end of the play. And a crucial moment in this process comes early in Act I, after the derisive laughter of the actors has died down somewhat, and the Father explains that “we want to live, sir . . . only for a few moments – in you.” In response, a young actor says, pointing to the Stepdaughter, “I don’t mind. . . so long as I get her.” This comically libidinous response is ignored by everyone on stage, but it represents an important turning point in the minds of the actors in the company and in the minds of the audience as well. It embodies a playful, tentative acceptance of the illusion, a making do with what’s available, an abandonment to the situation as it presents itself. In short, it represents the response to the mystery of life to which human beings obsessed with absolute certainty are ultimately reduced. One must simply get on with life and make the best of it, accepting the hopelessness of trying to draw fine distinctions between what is real and what is not.

Comedy

A less obvious device in the play is Pirandello’s use of laughter to lighten the audience’s confrontation with this frustrating collision of reality and illusion. The play is not easily seen as humorous on the page, but in production the humor can be rich and is certainly essential in order to reassure the audience that their inability to easily distinguish between reality and illusion is an inevitable but ultimately comic part of human existence. The humor is most obvious in the frustrations of the acting troupe. Serious but self-important, they are comical in their inability to deal with anything they are too inflexible to understand. The Producer is admirable in the way he finally bends to the unusual situation and vaguely sees the emotional intensity that the “characters” have brought to him. But he is ultimately comical because he is hopelessly obsessed with stage conventions. He insists on trying to “fit” this phenomenon within the boundaries of what he’s most familiar with and his efforts are comically doomed. In the Edward Storer translation of Pirandello’s original text, the play ends with the Producer throwing up his hands and saying “never in my life has such a thing happened to me.” What often makes comedy rich is witnessing human beings forced into being resilient under the common, existential circumstance of confronting the ultimate mystery of the universe. But the play also displays a grim kind of humor in the desperation of the “characters,” who stumble across this rehearsal looking for an “author” and end up settling for a director with decidedly commercial tastes. The Producer is not an author who can complete their story but someone who depends on a script that’s finished. The best that he can do is to exemplify the incompleteness the “characters” have brought him; the worst he can do is to create more barriers to their sense of an accurate portrayal of their story, which he what he most comically does. The Father and Stepdaughter laugh when the actors portray them so differently from the way they see themselves, but the joke is ultimately on them. At the very beginning of the play, the Producer is complaining of the obscurity of Pirandello’s Rules of the Game. He is satirically instructing his leading actor that he must “be symbolic of the shells of the eggs you are beating.” It is a very funny moment, given the actors’ and Producer’s frustration, as well as Pirandello’s playful self-denigration. But it is also a moment filled with rich comic ambiguity because the Producer’s dismissive explanation is quite seriously what Pirandello’s play is all about:“(the eggs) are symbolic of the empty form of reason, without its content, blind instinct! You are reason and your wife is instinct: you are playing a game where you have been given parts and in which you are not just yourself but the puppet of yourself. Do you see?… Neither do I! Come on, let’s get going; you wait till you see the end! You haven’t seen anything yet!”

Critical overwiev

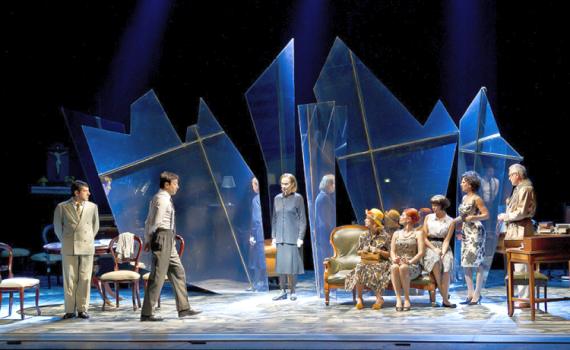

The first production of Six Characters in Search of an Author at the Teatro Valle in Rome on May 10, 1921, astonished its unsuspecting audience. As Gaspare Giudice reported in his biography of Pirandello, “things started to go badly from the first, when the spectators came into the theatre and realized that the curtain was raised and that there was no scenery.” Some spectators considered this “gratuitous exhibitionism,” especially as it was yoked with stagehands and actors milling about as if they were not really in a play. The arrival of the “characters” was even more “extraordinary” and “all this was enough to infuriate anyone who had gone to the theatre to spend a pleasant evening. The first catcalls were followed by shouts of disapproval, and, when the opponents of the play realized that they were in the majority, they started to shout in chorus, ‘ma-ni-co-mio’ (‘madhouse’) or ‘bu-ffo-ne’ (‘buffoon’).” The production had its supporters, but their defense of Pirandello’s play created even more confusion, and the audience members, actors, and critics ended up exchanging blows that even spread out into the street and into a general riot after the play had ended. Cooler heads ultimately prevailed, led perhaps by the review the next day by Adriano Tilgher, who would later become one of the most important and influential critics of Pirandello’s work. Tilgher pronounced that the production was “a success imposed by a minority on a bewildered, confused public who were basically trying hard to understand.” Tilgher concluded that “from today, we can say that Pirandello is most certainly among the leading creators of a new spiritual environment, one of the most deserving precursors of tomorrow’s genius if tomorrow ever comes.”

A few months later the production was remounted in Milan and because of the intervening publication of the text, audience and critics were prepared for the play’s radical innovations of style and theme. Over the next three years, Six Characters in Search of an Author was produced successfully all over the world. An especially important production of the play directed by Georges Pitoeff was mounted in Paris on April 10, 1923. The production had, according to Thomas Bishop, “the effect of an earthquake.” Most famous for Pitoeff s ingenious device of bringing the characters down onto the stage in an elevator, the production created “characters” who were deemed “supra-terrestrial,” and Germane Bree followed the famous French dramatist Jean Anouilh in saying that because of the influence that Pirandello had on generations of French dramatists “the first performance of Pirandello in Paris still stands out as one of the most significant dates in the annals of the contemporary French stage.”

Another very important production of the play occurred in Berlin in December, 1924. Directed by the legendary Max Reinhardt, the characters were on stage from the beginning of the play but hidden from the audience until, as Olga Ragusa described it, “a violet light made them appear out of the darkness like ‘apparitions’ or ghosts.” The production was said in a review by Rudolph Pechel to have fully realized “the magnitude and the possibilities of (Pirandello’s) theme.” According to Pechel, “it was Max Reinhardt rather than Pirandello who was the poet of this performance” because “Reinhardt felt the potential of this piece and offered a master production of his art in which the audience became fully aware of all the horror of this gloomy world.” According to Pechel, the “characters” were “like departed souls in Hades yearning for life-giving blood.”

In 1925 Pirandello’s own theatre company took the play to London as part of its world tour and the play was performed in Italian because the British censors had objected to the play’s references to incest. A reviewer for the London Times maintained that in Italian “the tragic personages are more tragic, the squalid personages more squalid, and the comic remnant more emphatically and volubly comic.” He called it “a new theatrical amusement. For it is certainly amusing to see characters disintegrated, as it were, on the stage before you, wondering how much of them is illusion and how much reality, and setting you pondering over these perplexing problems while enjoying at the same time the orthodox dramatic thrill.” A reviewer for the Manchester Guardian simply proclaimed the production “a dramatized version of a first-year course upon appearance and reality” in which “the author’s strength lies not in any philosophical brilliance but in the practical cunning whereby he as made metaphysics actable.”

Between 1922 and 1927 productions of the play appeared throughout Europe, the United States, and even in Argentina and Japan, testing directors, audiences, and critics around the world. As a result of the many rich responses to his work, Pirandello fashioned a significantly revised version of his play in 1925 in which he suggested the use of masks for the “characters” and appended his famous “Preface” that reveals the genesis of the work and Pirandello’s concept of its thematic elements. Today, the “Preface” remains an almost integral part of the play itself. Important productions around the world continued throughout the decades following Pirandello’s death, including a New York production in October, 1955, adapted and directed by Tyrone Guthrie and a three-act opera version that appeared in New York in 1959 with a libretto by Denis Johnston and a score by Hugo Weisgall. As Antonio Illiano reported, Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author “was like a bombshell that blew out the last and weary residues of the old realistic drama” and today it is widely considered one of the most important and influential plays in the history of twentieth-century drama.

Criticism

Terry R. Nienhuis

Nienhuis is a Ph.D. specializing in modern and contemporary drama. In this essay he discusses the role that uncertainty plays in Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author.

Pirandellian themes like the relativity of truth, the constantly changing nature of personal identity, or the difficulty of distinguishing between reality and illusion or between sanity and madness all have a common thread – they all point to uncertainty as a significant part of human experience. As John Gassner has observed, Pirandello was consistently “expressing a conviction that nothing in life is certain except its uncertainty.”

In Six Characters in Search of an Author uncertainty begins with the introduction of the “characters.”

The claim they make about their reality is obviously counter to fact (they are, of course, actors), but Pirandello makes their case so convincing that it is ultimately difficult for the audience to feel certain about what they know to be true.

It is interesting to see how Pirandello does this.

First of all, Pirandello has encouraged the audience to adopt their customary willingness to suspend disbelief and accept the stage illusion as reality. As one-dimensional as the members of the theatrical troupe ultimately appear to be, the play seems to begin in a spirit of ultra-realism – with a stage hand nailing boards together (how mundane is the sound of a hammer meeting a nail), with a set that appears unprepared for a formal “show,” and with actors improvising their lines so as to sound as authentic as possible.

Therefore, if the audience has taken these initial characters for real, what must they do with a group that claims they are even more real than the actors in the Producer’s troupe? And the “characters” persist in their claim with such a vehemence that their claim becomes compelling.

Contemporary jurisprudence demonstrates a similar phenomenon. No matter how certain a defendant’s guilty conduct seems to be, if the person charged with a crime persists in claiming innocence an air of uncertainty eventually envelops the proceedings and significant numbers believe the defendant innocent.

In this way, the Mother is especially difficult for the audience to dismiss as “merely an actress” because she is so simple and direct in her assumption of “reality.” As Pirandello says in his “Preface,” the Mother “never doubts for a moment that she is already alive, nor does it ever occur to her to inquire in what respect and why she is alive. . . . she lives in a stream of feeling that never ceases.” And perhaps her most powerful moment comes near the end of Act II when the Producer verbalizes a very common sense approach to her suffering. The Producer is willing to grant the Mother some kind of reality but points out that if her story has happened already she should not be surprised and distraught by its reoccurrence. But the Mother says, “No! It’s happening now, as well: it’s happening all the time. I’m not acting my suffering! Can’t you understand that? I’m alive and here now but I can never forget that terrible moment of agony, that repeats itself endlessly and vividly in my mind.”

In spite of the collision with common sense that this assertion entails, intensity like this makes the fiction so compelling that the audience is forced to question its own certainty, if only subconsciously and only in a flashing moment. The genius of Pirandello is that he calls attention to the illusion and at the same time helps to perpetuate it, thereby demonstrating the awesome power that illusion has over the human mind and the inevitable state of uncertainty that must result.

An even more obvious contribution to the audience’s sense of uncertainty is that Pirandello allows different versions of events to be presented but never suggests which might be more near the “truth.”

Under what circumstances, for instance, did the Mother leave with the Father’s secretary? Did she leave of her own accord? Or was she forced to leave? What were the Father’s feelings for his stepdaughter while the young girl was growing up? What actually happened in the brothel? The Father, Mother, and Stepdaughter all answer these questions differently but there is no adjudication. In fact, the resolution of the different versions is simply ignored and becomes moot as the play ends in the melodramatic drowning and suicide. And Pirandello makes clear that the resolution would be impossible anyway because uncertainty is at the heart of language itself.

In Act I the Father says, “we all have a world of things inside ourselves and each one of us has his own private world. How can we understand each other if the words I use have the sense and the value that I expect them to have, but whoever is listening to me inevitably thinks that those same words have a different sense and value, because of the private world he has inside himself too. We think we understand each other; but we never do. Look! All my pity, all my compassion for this woman (Pointing to the Mother) she sees as ferocious cruelty.”

After one examines how Pirandello puts his audience into this condition of uncertainty, the next question is why does he choose to do this? In part, he creates uncertainty in his audience because he believes uncertainty is the natural condition that human beings must learn to live with. In his famous essay, “On Humor” (1908), Pirandello summed up this attitude toward human existence, asserting that “all phenomena either are illusory or their reason escapes us inexplicably. Our knowledge of the world and of ourselves refuses to be given the objective value which we usually attempt to attribute to it. Reality is a continuously illusory construction.”

Consequently, the “humorist,” or artist, sees that “the feeling of incongruity, of not knowing any more which side to take,” is the feeling he or she must create in the audience. Illusions are the human attempt to create certainty where it doesn’t really exist, and all fall prey to the temptation. Pirandello’s art simply puts many of mankind’s most common illusions on center stage to demonstrate their flimsy inadequacy and encourages the audience to recognize these illusions for what they are. Pirandello describes life as “a continuous flow,” with logic, reason, abstractions, ideals, and concepts acting as illusory constructs that attempt to fix this flux into a reality that can be stabilized and more certainly known. But Pirandello concludes that “man doesn’t have any absolute idea or knowledge of life, but only a variable feeling changing with the times, conditions, and luck.”

Umberto Mariani has asserted that the typical character in a Pirandellian work of art “has lost the feeling of comforting stability” and chafes under the “tragic knowledge that he cannot achieve what he seeks and needs; a universe of certainties, an absolute that would allow him to affirm himself.” Robert Brustein observed that “(For Pirandello) objective reality has become virtually inaccessible, and all one can be sure of is the illusion-making faculty of the subjective mind.”

Brustein noted that “man is occasionally aware of the illusionary nature of his concepts; but to be human is to desire form; anything formless fills man with dread and uncertainty.”

Aureliu Weiss has summarized all of this most abruptly, asserting that Pirandello simply “derided human certainty and denounced the fragility of the truth.” But Weiss has also brought this discussion of content back around to its ultimate focus on form. When everything seems uncertain, “such a concept cannot be expressed through the traditional forms. It needs its own style… What was needed to succeed in such an enterprise… was to strike an initial blow strong enough to shatter our certainty… to create an atmosphere where reality would become less concrete and where illusion could play freely and gently worm its way into the audience’s consciousness. No longer sure of anything, the spectator would accept as normal the oscillation between reality and illusion.”

But Pirandello’s obsession with uncertainty can also be accounted for by a basic understanding of the intellectual history of the Western world – which has witnessed a gradual erosion of certitude, from a relatively high degree of certainty in the Medieval world to the relatively high degree of uncertainty in the 20th century.

Propelled, ironically, by the discoveries of science, this process has been developing for hundreds of years and has simply culminated in the implications of Darwin, Freud, and Einstein, among others.

Anthony Caputi, in his Pirandello and the Crisis of Modern Consciousness, asserted that “Pirandello began where Matthew Arnold began, with the conviction that the world was in disarray, that the system of beliefs that had provided coherence and continuity for centuries had broken down, and that the new sciences could yield little more than organized barbarism.”

What Caputi called “the crisis of modern consciousness” is “that stage in which not just traditional ways of deriving coherence and value were lost but the capacity for deriving alternative coherences by way of the reason has been undermined as the reason itself has been subverted as an authority. As the idea gained ground that every mind is a relative instrument, subject not to the grand program for coherence provided by Christianity or, for that matter, by any other traditional orthodoxy, but subject to its own conditions, a new variability and a new insecurity were born. Not only did men and women not look to external sources for guides to value, they no longer looked to reason.”

As Renato Poggioli put it, “logic, or reason, according to the classics of philosophy, had always had a universal value, equally valid for each individual of the human race.”

But “Pirandello does not believe in reason as an absolute and transcendent value.”

Reason for Pirandello is simply “a practical activity,” a tool the mind uses as it needs to create and defend its illusions.

Pirandello was the dramatist of consciousness, examining how the human mind apprehended the world, and he decided that humans could be certain of nothing that was produced from such a variety of mental platforms.

The old standards of “reason” and “logic,” thought to be constant guides implanted by God in the minds of all human beings, were dead, to be replaced by the disconcerting phenomenon of relativism.

In a process of questioning that began most vigorously in the Renaissance, all that had been taken as certain for centuries was gradually re-examined until finally the process of consciousness itself fell under scrutiny and humans discovered that the workings of the mind delivered more tricks than dependable conclusions.

As Caputi finally put it, Pirandello and “most of the artists and writers of the (twentieth) century” saw the human mind as “a frail, uncertain faculty capable of little more than self-deception.”

John Gassner concluded that Pirandello’s “work remains a monument to the questioning and self-tormenting human intellect which is at war… with its own limitations. Once the intellect has conquered problem after problem without solving the greatest question of all – namely, whether it is real itself rather than illusory – it reaches an impasse. Pirandello is the poet of that impasse. He is also the culmination of centuries of intellectual progress which have failed to make life basically more reasonable or satisfactory. He ends with a question mark.”

And Robert Brustein concluded by saying that “after Pirandello, no dramatist has been able to write with quite the same certainty as before.”

Source: Terry R. Nienhuis, for Drama for Students, Gale, 1998.

1921 – Six characters in search of an author

A comedy in the making in three acts

Introduction, Analysis, Summary

Pirandello’s preface

Characters, Act I

Act II

Act III

In Italiano – Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore

En Español – Seis personajes en busca de autor

Se vuoi contribuire, invia il tuo materiale, specificando se e come vuoi essere citato a

collabora@pirandelloweb.com